Felix Liebermann (1851–1925) was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin. He grew up only metres from the Brandenburger Tor in central Berlin with his parents and three siblings, which included the famous painter Max Liebermann. His father wanted him to enter the family business in textile manufacturing, so after finishing school Felix trained at a bank in Berlin before being sent to Manchester to work in the textiles industry (1870–1872).

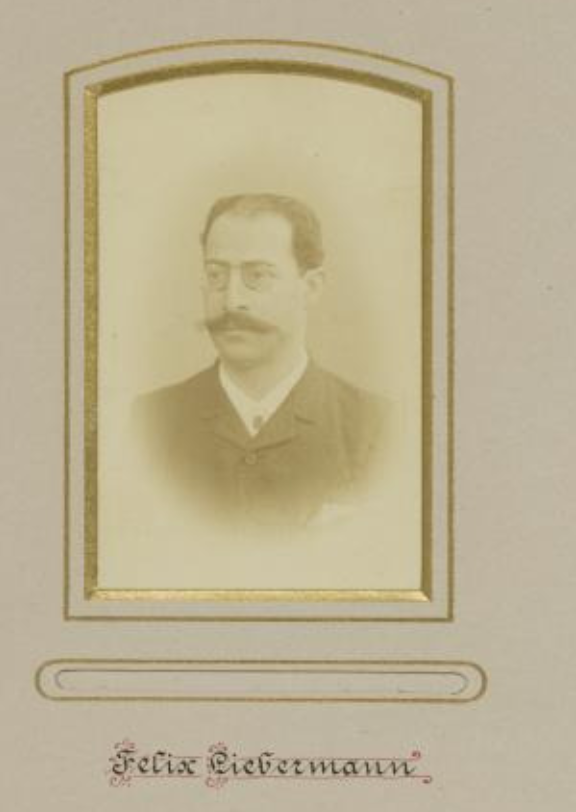

A young Felix Liebermann, painted by his brother

A young Felix Liebermann, painted by his brother

Education and MGH

When or how he became interested in history – English history in particular – is uncertain, though letters from his brother Max suggests he was reading history in the evenings in while working in the merchant industry.1 On returning to Germany, and after a year’s military service, he convinced his father to let him study history. He went to Göttingen, where he took courses in English history with Reinhold Pauli and German history with Georg Waitz. In 1875–6, he attended lectures in Berlin with, inter alia, Theodor Mommsen on Roman law and Rudolf von Gneist on German constitutional law.2 His thesis on a twelfth-century legal text, Einleitung in den Dialogus de Scaccario, was published in 1875 and he was awarded his doctorate in January of 1876.

For the next decade or so, Liebermann worked at the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, where one of his Göttingen professors, Georg Waitz, had recently taken up the editorship.3 Liebermann collaborated with Reinhold Pauli on volumes 27 (1885) and 28 (1888), completing them alone after Pauli died in 1882. These volumes collected historical writings on Germany from England, and so during this time, Liebermann spent long periods in England doing manuscript work. Though mostly on the clock for the MGH, he also found time to do his own work, resulting in the 1879 volume Ungedruckte Anglo-normannische geschichtsquellen.

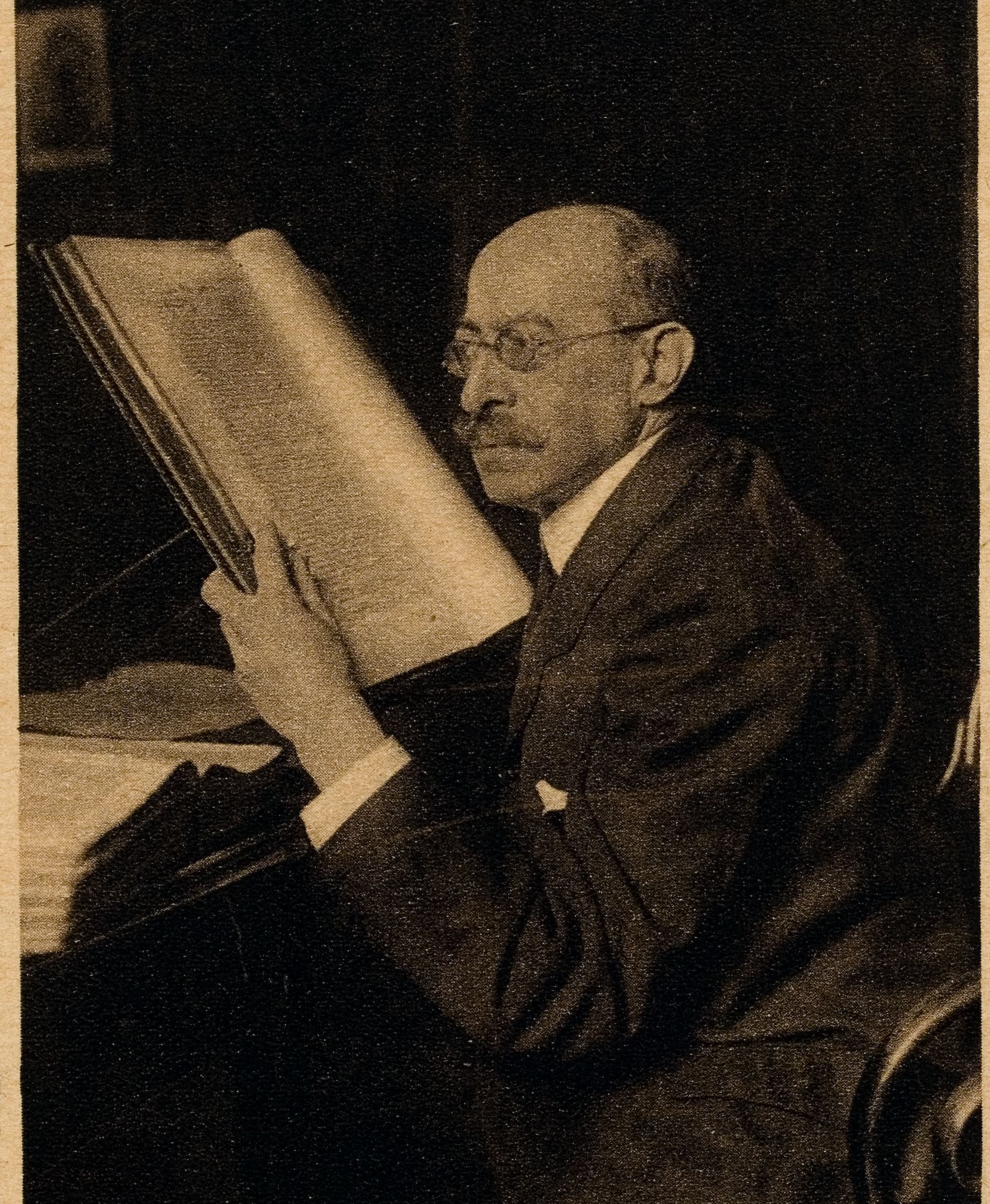

A picture of Felix during his time at the MGH, from this book

A picture of Felix during his time at the MGH, from this book

The Anglo-Saxon laws

Felix soon turned to Anglo-Saxon sources too. In 1883, he had been given a commission to re-edit the Anglo-Saxon laws by the Savigny-Stiftung, at the behest of Heinrich Brunner and Konrad Maurer, who considered extant editions inadequate, given that the previous edition (while good) had been prepared without the editor ever seeing one of the manuscripts.4 In 1884, Felix published some initial research from the manuscripts in the article ‘Zu den Gesetzen der Angelsachsen’ in Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte.

But first he had to finish his work for MGH, which took until 1888, and in 1889, he published some further labours from his manuscript work in England, namely the Old English and Latin texts of ‘On the resting places of saints’ (Secgan) and ‘The Kentish royal legend’ (Þa halgan) in Die Heiligen Englands.

Only then did he turn to his greatest work, the three-volume edition of the Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman laws, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. He published several of the Anglo-Norman laws and other small studies as articles in the 1890s, but the complete printed edition of the texts came out in 1903, with the second volume following in 1912 and the third in 1916.

Liebermann’s edition contains all law-texts written between the seventh and twelfth centuries in Kent, Wessex and England, whether in Latin or Old English. He also included almost every manuscript version of these texts, printed in parallel columns, with further variants and emendations in the apparatus. He consulted many more manuscripts than any editor of the laws before him (again spending long periods in English libraries), which resulted not only in better texts than previous editions but also in new pieces that had not been printed before. Volumes two and three consist of a glossary of words (Wörterbuch), glossary of legal concepts (Sachsglossar) and introduction to each text. Though Liebermann insisted in letters to colleagues that he was no philologist, this edition has secured his legacy primarily as a textual critic.

Liebermann published widely on other subjects too in this period, much of it in the form of reviews or shorter notes. In addition to English legal history, he wrote about Beowulf and other Old English poems, the history of English national assemblies, Shakespeare, contemporary politics and much more. A bibliography of his works collected by Harald Kleinschmid in the 1980s lists 650 items, ranging from single paragraph notes to the three-volume edition.

Scholarly network

His wide-ranging interests are reflected in the range of academics he corresponded with, mainly in Germany and in England.5 Among his correspondents we find, for instance, Henry Bradshaw (librarian Cambridge UL), Alois Brandl (philologist, Germany), Karl Brinkmann (sociologist and economist, Germany), Heinrich Brunner (legal historian, Germany), Paul de Lagarde (orientalist, Germany), Max Förster (philologist, Germany), Harold Hazeltine (historian, England/US), Andreas Heusler (philologist and legal historian, Switzerland/Germany), F.W. Maitland (legal historian, England), Wolfgang Michael (historian, Germany), George Neilson (historian, Scotland), George Prothero (historian, England), Edward Schröder (medieval historian, Germany), William George Searle (historian, England), Eduard Sievers (philologist, Germany), William Stubbs (historian, England), T.F. Tout (historian, England), Karl von Amira (legal historian, Germany), and Georg Waitz (historian, Germany).

Liebermann also received numerous books and articles from colleagues.6 His library contains at least 300 books sent to him by around 150 different authors, including George Burton Adams (11 items), Mary Bateson (3), Heinrich Brunner (9), Alexander Bugge (1), Helen Maud Cam (1), Léopold Delisle (2), Udo Eggert (1), Wilhelm Foerster (1), E.A. Freeman (2), F. Frensdorff (6), Otto von Gierke (1), Charles Gross (6), Hubert Hall (6), Charles Homer Haskins (6), Harold Hazeltine (5), Wilhelm Levison (4), Maitland (5), Lorenz Morsbach (6), George Neilson (5), Frederick Pollock (8), Hugo Preuss (4), Ludwig Riess (5), J.H. Round (8), Kenneth Sisam (2), Johannes Steenstrup (5), Paul Vinogradoff (6), and many more. This doesn’t necessarily imply closeness on the part of the senders and Liebermann – though it shows that he was part of a large scholarly network.

Liebermann was also important in his network as a mediator between English scholarship and German scholars. For instance, he wrote several long articles summarising recent work in English history for German journals and advising German scholars on manuscript work in England and Ireland.7 He received letters with questions on all aspects of Old English texts and English scholarships and wrote long letters in reply. Liebermann championed the work of English legal historians like Stubbs, Maitland and Tout in Germany and lamented the ignorance of German scholarship in England. When Alois Brandl concluded his obituary of Liebermann with the question “Wie wird es jetzt unseren altenglischen Studien ergehen?”, it might well refer to his role in disseminating knowledge through letters, reviews and private conversations in his home in Bendlerstrasse.8

Universities and Liebermann

Liebermann was given the title of Professor by the Prussian government in 1896, held honorary degrees at Oxford (1909) and Cambridge (1896), and was a corresponding member of the British Academy (1909), Royal Historical Society, Jewish Historical Society of England, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften (1908) and Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen (1908).

He never worked at a university. According to an obituary, this was because of a slight speech impediment, and he was wealthy enough to continue his work outside the academy.9 However, it’s worth bearing in mind how difficult it could be for Jewish academics to get positions in German universities at this time. And there are some signs that he would have wished to. For instance, he wrote in a letter to Edward Schröder, who had been behind his nomination and appointment as corresponding member in Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen:

“When, like you, one is firmly established as a university lecturer among colleagues, with the opportunity to discuss the issues that concern one on a daily basis and to receive the opinions and perhaps advice of like-minded colleagues after the publication of a paper, such an honour may seem just like any other pleasant aspect of teaching. I, on the other hand, truly feel that this correspondence is my admission into a circle of like-minded friends, which I otherwise completely lack in my life.”10

It’s also clear that he took a great interest in teaching. According to an obituary Liebermann wrote to Hazeltine that “among all the human callings there is none like teaching”.11 His library also reveals an interest in teaching, with several articles and books on the topic. For instance, Liebermann has underlined and annotated an article which sets out the practicalities of lecturing (should you have notes, how quickly should you speak and so on) from the volume Essays on the Teaching of History.12 Perhaps he supervised informally, for Frank Zinkeisen addressed Liebermann as his ‘geschätzten Lehrer’ in a handwritten inscription in the copy of his dissertation which he sent to Liebermann.13

Non-academic activities

In a note about Felix in Wer ist’s (Who’s who) of 1905, he described his three favourite pastimes as ‘Lesen schöner Litteratur, Sehen von Kunst, Fürsorge für Arme’, interests he had the time for given his freedom from teaching and other university duties.14 With his siblings, he set up Louis Liebermann Stiftung für die Armen Berlins after their father’s death in 1894 and with his wife Cäcilie he started a charitable foundation (Cäcilie- and Felix-Liebermann Stiftung) in 1905. He also donated money to children’s hospitals, orphanages and to support Jewish students.15

Liebermann’s Jewish identity was an important part of his life. He was involved in the running of the Zunz-Stiftung zur Förderung und Ausbreitung der Wissenschaft des Judentums and was chairman of the Salomon-Neumann-Stiftung fur die Wissenschaft des Judentums.16 He wrote a few articles for Jewish magazines and was interested in work on Jewish history.17

Several memorials of Liebermann notes that he was proud of his Jewish identity, though that he was uninterested in religious disputes.18 Ludwig Geiger, in a tribute to Liebermann on his sixtieth birthday, wrote that “While he lived according to traditional precepts out of respect for his parents and in-laws, he always maintained his own independent views on the nature and development of the religion.”19

Another interest was in politics and social reform. In his youth, he described himself as a National Liberal,20 though he rarely discussed party politics later. However, his library reveals that he read widely on current political and social issues throughout his life, including many of the books and pamphlets issued by the Gesellschaft für Soziale Reform. He occasionally wrote articles for Ethische Kultur: Monatsblatt für ethisch-soziale Neugestaltung,21 and assisted in setting up the organisation’s reading room.22

The First World War

The first world war was a disaster for Liebermann as a scholar and person. Not only was he cut off from his colleagues and friends in England, but he was also bitter and resentful at their attitudes and, in general, at the hatred towards Germany found in England and the English press. He fully supported Germany’s efforts, joining his fellow countrymen in blaming England for the outbreak of war. However, unlike many of his academic colleagues, Felix refrained from signing the ‘Manifesto of the 93’ (An die Kulturwelt!) in October 1914, believing it to be a bad idea. However, to his disappointment, the English press had apparently reported that he did (believing him to be the ‘Prof Liebermann’ on the list of signatories, while this was in fact his brother Max). This lost him more friends and colleagues.23

He alienated more of his British colleagues with his dedication to the third volume of Gesetze (1916):

“…trusting hope that the storm of hatred and the sea of blood that rage around the time of the completion of these pages may soon be understood as essentially caused by the … clash between the ruthless claims of a world empire accustomed to power, to dominate seafaring and world trade alone, and the justified decision of the united German people to strive for the goods of this earth peacefully and prudently…”.

He also expressed a desire for reconciliation and looked back at the days of collaboration between German and English scholars, but in the eyes of his English colleagues this was overshadowed by the belligerency of the dedication.24

In 1917, Liebermann was struck off as a member of the Royal Historical Society, alongside other ‘Enemy-Members’ from Germany and Hungary. Only those who had ‘dissociated themselves explicitly from the late political and military action of their countries’ were kept.25 This did certainly not include Liebermann. He felt this so unfair that he also refused to be reinstated after the war, though he eventually was in April 1924.26

Liebermann’s scholarly life was put more or less on hold during the war. He signed up to help the war effort as soon as the war broke out, but he was not called upon until 1916 when he was set to extract information from British weekly, fortnightly and quarterly publications.27 He mentions that this work kept him from his academic work, though elsewhere he describes being too depressed to work.28 However, he certainly engaged with academic writing relating to the war. His library contains many war-time pamphlets written by German academics, which Liebermann underlined and annotated heavily. Liebermann himself published in non-academic journals about the war and expressed his opinions frequently in academic journals through reviews of books about the war or books about England written in Germany during the war.

After the war, he resumed correspondence with a few English historians, including George Prothero and Tout, though the relationships seem rather strained. Nevertheless, after his death in 1925, several very positive obituaries appeared from British scholars. And towards the end of his life, he continued to publish on English literature and history, including Beowulf, the canons of Theodore, Nennius and medieval political history.

On 7th October 1925, Felix Liebermann was hit by a car outside his home and died a few hours later.

Further reading:

-

Amira, Karl von, ‘Felix Liebermann’, Jahrbuch der Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften (1926)

-

Brandl, Alois, ‘Felix Liebermann’ in Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen 150 (1926): 1–5.

-

Hazeltine, Harold, ‘Felix Liebermann 1851–1925’, Proceedings of the British Academy 24 (1938): 319–359.

-

Heymann, Ernst, ‘Felix Liebermann’, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte - Germanistische Abteilung 46 (1926): 23–39.

-

Kleinschmidt, Harald, Felix Liebermann 1851–1925, Bibliographie seiner Schriften (Stuttgart, 1983).

-

Ostwald, Hans, Das Liebermann-buch (Berlin, 1930).

-

Rabin, Andrew, ‘Felix Liebermann and Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen’, in Stefan Jurasinski et al. (eds), English Law before Magna Carta: Felix Liebermann and Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen (Leiden, 2010), pp. 1–8.

-

Sandig, Marina, Felix Liebermann: Mittelalterhistoriker — Gelehrter — Mäzen (Leipzig, 2024).

-

Tout, T.F., ‘Felix Liebermann (1851–1925)’, History n.s. 11 (1926): 311–319.

-

Wormald, Patrick, ‘Felix Liebermann’, in John Cannon et al. (eds) The Blackwell Dictionary of Historians (New York, 1988), pp. 245–247.

-

Ostwald, Das Liebermann-buch, p. 101. ↩

-

Marina Sandig, Felix Liebermann: Mittelalterhistoriker — Gelehrter — Mäzen (2024), pp. 26, 65 gives these dates based on university records, though note that Hazeltine’s obituary says Liebermann was at Berlin in 1872-3. ↩

-

A new book has recently been published on Jewish MGH associates, which has a chapter on Liebermann. Unfortunately I have not been able to see this yet! ↩

-

Karl von Amira, ‘Felix Liebermann’, Jahrbuch der Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften (1926). Reinhold Schmid, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen, p. viii. ↩

-

Unfortunately, no collection of letters sent to Liebermann has survived. I have found 14 letters addressed to Liebermann, some preserved in books in his library and some printed in Letters of William Stubbs. I have found over 130 letters from Liebermann that relates to his academic work, mostly preserved in the private papers of his correspondents as well as in the MGH archive. There is also a much larger archive of letters Liebermann sent as part of his work for the Zunz-Stiftung. ↩

-

This evidence comes from the relevant books in his library, currently held at the University of Tokyo. Some books/articles have short notes written by their authors to Liebermann, others have a note in Liebermann’s hand saying he received it from the author. ↩

-

See the issues of Deutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft in 1889–1893. ↩

-

Alois Brandl, ‘Felix Liebermann’ in Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen 150 (1926), p. 5. ↩

-

Ernst Heymann, ‘Felix Liebermann’, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte - Germanistische Abteilung 46 (1926): 23–39. ↩

-

Letter to E. Schröder, 22.2.1909,Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen https://kalliope-verbund.info/DE-611-HS-3235680 ↩

-

Harold Hazeltine, ‘Felix Liebermann 1851–1925’, Proceedings of the British Academy 24 (1938): 319–359. ↩

-

H.M. Gwatkin, ‘The teaching of ecclesiastical history’, in F.W. Maitland et al., Essays on the Teaching of History (1901), Tokyo University Library, call no: G000:182. ↩

-

Frank Zinkeisen, Die Anfänge der Lehngerichtsbarkeit in England (1893), Tokyo University Library, call no: L520:607. ↩

-

Sandig, p. 42. ↩

-

Sandig, p. 42. ↩

-

Liebermann wrote several articles for the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums during the war, including ‘Noch einmal der englische Zionismus’ (issue 81.10, 9.3.1917) and ‘Wenn ich neutraler wäre’ (issues 80.29/30 14 & 21.7.1916). He also contributed notes on Jewish history to Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums, e.g. ‘Juden in England, aus Deutschland eingewandert’ (vol. 55 (March/April 1911), p. 253) and ‘Elisabeth von Englands jüdischer Agent in Konstantinopel’ (vol. 53 (September/Oktober 1909), p. 634, 749). ↩

-

Ismar Elbogen, ‘Felix Liebermann’, Central-Verein-Zeitung: Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum 42, 16.10.25. Anonymous birthday tribute to Liebermann in Allgemeine Zeitung der Judentums 14 (8.7.1921). ↩

-

L. Geiger, ‘Professor Felix Liebermann’, Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums 75 (1911) [21.7.1911], pp. 341–2. ↩

-

Letter to Paul de Lagarde, 22.10.1879, Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen https://kalliope-verbund.info/DE-611-HS-3171746. ↩

-

‘Wie England unser Feind wurde’, Ethische Kultur 1.11.1914, ‘Beim Frieden keine Rücksicht auf Opfer und Rache!’ Ethische Kultur 1.10.1916, ‘Sollen wir uns von der Kleidung befreien?’ Ethische Kultur 15.3.1925. ↩

-

Paul Jaffé, ‘In memoriam Felix Liebermann’, Ethische Kultur 15.11.1925. ↩

-

Letter to Karl von Amira 3.8.1921, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek http://kalliope-verbund.info/DE-611-HS-558354] ↩

-

e.g. Tout, ‘Felix Liebermann (1851–1925)’, History n.s. 11 (1926), p. 318. ↩

-

‘Report of the Council, Session 1917-18’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 2 (1919): 199-205, at 203. ↩

-

Letter to Prothero, 10.11.1921, RHS Archive’s Prothero Collection. ↩

-

Letter to E. Schröder 7.4.1917, Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen https://kalliope-verbund.info/DE-611-HS-3235680 ↩

-

Letter to E. Schröder 7.4.1917; letter to Harry Bresslau, 10.11.1919 MGH-Archiv B 698 https://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/archiv/b/B_00698.htm ↩