Felix Liebermann (1851–1925) is known mostly for his enourmous edition of the Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman laws. Der Gesetze der Angelsachsen came out in three volumes between 1903 and 1916. Volume 1 prints almost every manuscript version of each text, as well as a German translation, and Volumes 2 & 3 include commentary to the laws and explanations of words and concepts. It has all the information anyone might want (albeit in heavily abbreviated and difficult German).

Liebermann’s Gesetze is still many scholars’ go-to for editions of the laws, despite some of its flaws. Many texts exist in more recent editions (e.g. the early Kentish laws, the code of Alfred, Wulfstan’s laws for Æthelred and Cnut). But nothing quite rivals the convenience of having all texts printed from essentially every manuscript like you get in Gesetze.

WHO WAS LIEBERMANN?

Liebermann’s career has been covered before,1 but the short summary is that he was a historian from a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin, so wealthy, in fact, that he never needed to work a paid position at a university to continue his research (whether this was by choice or not I will deal with in a future post). He was a historian, first, of medieval England and later of Anglo-Saxon England. Though he didn’t have a degree in law, he started editing Anglo-Norman legal sources early in his career and continued to work on medieval law for the rest of his career. He started his editing career at the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, where he edited English sources alongside Reinhold Pauli and Georg Waitz. This led him to be commissioned to do an edition of the Anglo-Saxon laws, a project which took him almost 30 years. In addition to Gesetze, he published on everything from Anglo-Saxon material to Elizabethan. The vast majority of his publications are editions or source studies, but he also wrote many reviews, notes and non-academic articles.

There is a lot more to say about Liebermann’s life – for instance his philanthropic work, his intellectual context, his political opinions and his war-time experience – which I will do in future posts.

WHY TOKYO?

For now, let’s focus on Liebermann’s library and how it ended up in Tokyo, of all places. This collection of roughly 5000 items was sold after Liebermann’s death in 1925 and has been in Tokyo since 1927 or 1928. The details are unclear, since no records regarding this sale seem to have survived in Japan or Germany.2 What we do know is that it was bought by the Japanese Department of Finance using funds from the the Dawes plan, a scheme for German reparations set up in 1924. A catalogue drawn up by the University Library at the University of Tokyo in 1927 states that Liebermann’s library was bought in the fourth year of the plan (September 1927–August 1928). The first three annual payments had been used by Japan to get goods from Germany (e.g. cars), but in 1926 the Department of Finance decided to accept requests for books from Japanese universities.3 Liebermann’s library was one of these; other collections include those of Albert Osterrieth, Julius Hatchek, Andreas von Thur, Friedrich Thaner and Hugo Preuss (all of whom, except Thaner, died in 1925 or 1926).4

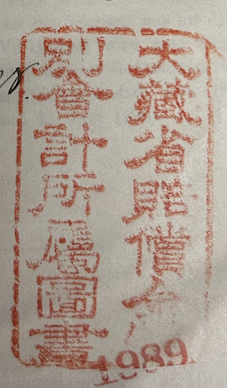

All the reparations books carry a stamp from the Department of Finance ( 大蔵省賠償金特別会計所属図書 “Books Pertaining to Department of Finance Special Account for Reparations”).

All the reparations books carry a stamp from the Department of Finance ( 大蔵省賠償金特別会計所属図書 “Books Pertaining to Department of Finance Special Account for Reparations”).

From surviving records from the Department of Finance, we see that some collections were specifically requested by academics in Japan. Others may have been chosen more at random from catalogues, which were sent from Germany to officials in Japan.5 The Japanese embassy or other intermediaries seem to have dealt with the actual purchasing and shipments back to Japan. So presumably Liebermann’s library was put up for auction by his wife and bought by intermediaries in Germany in 1927 or 1928.6

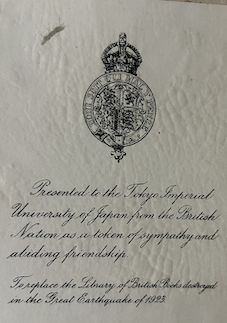

There are two relevant bits of context that also explain why Liebermann’s library ended up in Tokyo. First is the destruction of the library of the University of Tokyo in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The library thus needed a lot of new books. Many were gifted to the university from nations, libraries, universities and individuals across the world and other books were bought using the library restoration fund. But presumably the availability of reparations money at this particular time was opportune for Tokyo University and other universities that suffered losses. In Tokyo, none of the Dawes plan collections were kept intact as collections – the books were spread out across the normal holdings (as they still are today) – so presumably getting individual books to increase the general collection was the goal.

A lot of books in the UT library are donations from Britain after the earthquake.

A lot of books in the UT library are donations from Britain after the earthquake.

The second bit of relevant context are the decades-long ties between German and Japanese scholars. Starting in the late ninteenth century (but taking off after World War One), Japanese scholars and students made their way to Germany to study, especially medicine and law. In the late nineteenth century, foreign scholars were invited to work at Japanese universities, many of whom were German (including Ludwig Riess, a friend and colleague of Liebermann’s). In Japan, universities taught German and many German academic books were translated into Japanese. These ties survived the war. For example, Mitsubishi opened offices in Berlin in 1921, there was a Japanese fund which supported German scholars in financial hardship in the 1920s, and Japanese exchange students still chose Germany over other countries. In 1926 and 1927, Japanese-German cultural research centres were opened in Berlin and Tokyo.7

These connections also make themselves clear in the number of German scholarly collections in Japanese universities, which include many more than the ones bought with reparations money after the war. These include the libraries of Otto von Gierke (lawyer, legal historian), Otto Hirschfeld (ancient historian), Ernst Zitelmann (lawyer), Friedrich Stein (lawyer) and Christian L.E. Engel (statistician), to name some.8

As this suggests, a lot of the collections that ended up in Japan were of law and legal history books. So presumably this interest accounts for why Liebermann was chosen too. His library is well-stocked on the historical and literary front, but it also rich in books on law and legal history, both medieval and modern. I will post more about the content of Liebermann’s library soon!

-

See e.g. A. Rabin, ‘Felix Liebermann and Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen’, in Jurasinski, Oliver & Rabin (eds), English Law Before Magna Carta: Felix Liebermann and Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen Law (2010). ↩

-

See Hideyuki Arimitsu, ‘The Liebermann Library in Tokyo’ in Jurasinski, Oliver & Rabin (eds), English Law Before Magna Carta: Felix Liebermann and Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen Law (2010), who first drew attention to the existence of the library in Tokyo. He had not found any records in Japan at the time of writing that article. I have looked through (using trusted Google Lense) the Japanese digitised materials relating to the Dawes Plan purchases that year, which include records for the other collections, but not Liebermann’s. See the link in footnote 5. Marina Sandig, who has written a recent mini-biography of Liebermann, looked for records in Germany and the German embassy in Tokyo and found none (see Sandig, Felix Liebermann: Mittelalterhistoriker –Gelehrter – Mäzen (2024), pp. 57–8). The best we could hope for is perhaps to find the book catalogue/auction catalogue, which would presumably have been drawn up before a sale. ↩

-

For this and references to Japanese records, I have relied on this article. ↩

-

This useful database (also a book) has a list of all named collections in Japanese libraries. ↩

-

The 1937 catalogue states that it was bought for 45,000 Marks, which online calculators suggest might be around 200,000 Euros today (though I would take that with a pinch of salt). There are quite a lot of rare books, the oldest from 1494, so no wonder it was expensive. ↩

-

All the above is from K. Tetsuro, ‘Personal contacts in Japanese-German cultural relations in the 1920s and early 1930s’ in Spang & Wippich (eds), Japanese-German relations, 1895-1945: war, diplomacy and public opinion (2006), pp. 119-38. ↩

-

Though much more recent, medievalist might be interested to know that some 1500 books from J.W. Wallace-Hadrill’s library are also in Tokyo! ↩