King Edgar the Peaceful (r. 959–973) is well-known to most historians of early medieval Anglo-Saxon history. Not just for his role in the monastic reforms, patronage of the most powerful churchmen of the time or the glorious illustration of him from his charter to New Minster, but also for his laws. The most famous piece of legislation issued in his name is known as – in the clunky vocab of Anglo-Saxon legal historians – II-III Edgar.1 This law-code is praised for being systematic, detailed and structured. These might sound like qualities all law-texts should have, but it’s rare in the Anglo-Saxon corpus.

Personally, though, I have no particular interest in logically laid-out legislation that tells you the legal details you want to know. I prefer a textual puzzle, a text behind which there is clearly a hidden story of transmission, composition, survival or emendation.

Thankfully, Edgar has provided us with this as well! IV Edgar, or the Wihtbordesstan decree, is nothing like his earlier laws. In fact, it’s different from all other surviving Anglo-Saxon legislation in several ways. For instance, it opens with a line which is otherwise only found in charters: ‘Her is geswutelod on þisum gewrite..’ (‘It is declared here in this document…’). In one extant manuscript this line is even preceded by a cross, another feature of charters and writs.

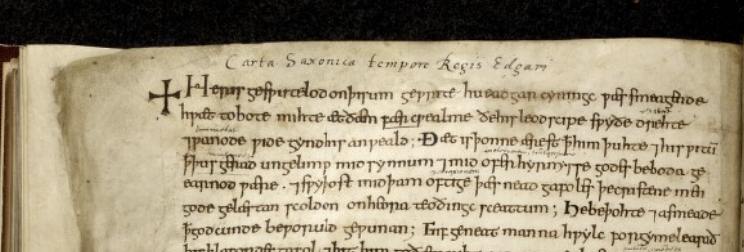

The opening of IV Eg (OE) in Cotton Nero E.i.

The opening of IV Eg (OE) in Cotton Nero E.i.

The main text of IV Edgar is also unusual, in that it opens with a long discursive section – almost a sermon, as you can see in translation here. Here the king tries to show how important it is to pay your church taxes by comparing God to a landlord who hasn’t received his rent after several reminders. You wouldn’t be surprised if he got angry, would you? Same with God, whose representatives on earth have constantly reminded people that they need to give God his dues.

The king’s motivation for getting people to pay their tithes, and so for issuing this bit of legislation at all, is that it is necessary for dealing with the ‘great pestilence’, the plague, currently killing his people. Sin and disobedience have consequences! That part might look strange to those who aren’t familiar with ninth- and tenth-century literature. But it’s hardly uncommon and so isn’t part of why this text is odd.

What stands out more about this text, in addition to the king’s lengthy story at the start, is the end. Here, the text stipulates that

one should write many documents about this and send either to ealdorman Ælfhere or to ealdorman Æthelwine and they should send it everywhere, so that the decree is known both to poor and rich.

This may sound like absolutely standard procedure when it comes to written law. But we never get anything like it stated explicitly, and on top of that, we aren’t even sure that written law was circulated particularly widely or was expected to be read.

Should we take the fact that this is included in the text to mean that this was an exceptional circumstance, that this decree, unlike most, should be sent around the country? Or should we assume that it was common; that something like this was often announced at meetings where law was made or proclaimed, but that it never usually made it into writing? Perhaps the scribe who produced the text that we now have was inexperienced – he didn’t realise that you could just leave that bit out.

It’s possible that decrees like IV Edgar were copied by several people at the same meetings. Representatives of different areas may have written down their own copies of proclaimed law, including things particularly relevant to them, leaving other things out. In fact, IV Edgar is more concerned with Danes and the Danelaw than most other surviving laws, though it is not issued just for the Danelaw. So perhaps we have the copy of someone from a Danelaw area who included all the bits about the Danes that a Wessex scribe (for example) might have left out.

The manuscript transmission of IV Edgar is very tenuous – both surviving Old English exemplars are copied from the same version. It hasn’t survived in any of the post-Conquest collections where most other Anglo-Saxon laws ended up. So this could tally with the extant text being a chance survival of a particular version.

If this was a standard procedure for the dissemination of Anglo-Saxon law, we’d perhaps expect to see some of survivals of different versions of other laws, which we (mostly) don’t.2 Though, in fact (and here we come to the strangest aspect of the Wihtbordesstan decree) we do have a second version of IV Edgar – in Latin.

IV Edgar Latin is, as far as I’m concerned, the most difficult text to explain in the corpus of Anglo-Saxon law. This is mostly because pretty much the whole corpus is in Old English (though with notable exceptions3).

Why does it exist at all? I can think of two possibilities.

One is that it represents a different version of the text from the same assembly meeting as the Old English version – either simultaneously translated during the assembly or perhaps translated from Old English afterwards. There is essentially no evidence for this, but it could explain the many differences between the two versions (it would be a very free translation if it were a translation). The Latin also leaves out some of the bits about the Danes, which would make sense if it represents the version taken down by someone from a district where that would be irrelevant. Why in Latin? Impossible to say, but perhaps it was intended for a bishop (who, according to II-III Edgar, sat as judges in some local courts). There is also more religous rhetoric (including a line from a psalm) in the Latin version, missing from the Old English version.

But given that Latin was the standard language for many other administrative matters for English kings in this period, it may also have been for a secular person. If it was merely the personal copy intended for one recipient, the language of the text could just reflect their preferences.

This is pure speculation.

The same goes for the other option, which seems more generally favoured (by the incredibly small number of people who are interested in this). The second theory is that IV Edgar Latin is a later translation from Old English into Latin, possibly by Archbishop Wulfstan of York (d. 1023). This scenario would also explain the many differences between the versions, since Wulfstan (who has left behind a huge amount of writing) had a tendency to play fast and loose when he copied or translated text. He loved to rewrite, usually by adding content-less intensifiers or other things that didn’t change the meaning of the original. However, he didn’t shy away from making more substantive changes to older laws either.4 The differences between the Latin and the Old English version of IV Edgar are mostly trivial in terms of the legal content, though there are a few instances where they diverge in legal detail too (see here for a commentary on some of the differences).

The origins for this theory is the fact that the Latin version of IV Eg survives in a “Wulfstan manuscript”. This term is often applied to manuscripts that had a connection to Archbishop Wulfstan, of which there are many. The manuscript in question (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 265) is probably a copy of a manuscript seemingly compiled by or for Wulfstan. Wulfstan didn’t compose most of the other texts in this manuscript (except one, known as the Handbook for a Confessor). Mostly it’s made up of Latin church law from England and the continent. It contains both the Old English and the Latin versions of IV Edgar, both of which look a bit out of place given the rest of the contents.

The most important unanswered question is why Wulfstan would translate this text at all – he didn’t do that to any of the other many Anglo-Saxon laws he had access to or included in his manuscripts. I haven’t found any instances of Wulfstan using IV Edgar as a source for his other laws, though the general topics of the text echo Wulfstan’s concerns (e.g. the importance of church dues, especially in preventing disasters). But IV Edgar certainly doesn’t seem to have been the most important old law-text for Wulfstan.

All in all, I can’t really imagine a way to prove, or even convincingly argue, for either of these options. Comparing the Latin of IV Edgar to Wulfstan’s other Latin text is the most promising method, though my own initial attempts haven’t revealed very much. Similarly, I don’t see any way to find out whether the Latin version stems from Edgar’s time or later. Felix Liebermann thought the Latin looked similar to the ‘pompous’ style of the late tenth century, but thought the text post-dated 975 (Edgar’s death), because it styles him ‘inclitus’ (famous) in the opening sentence. But that is not much to go on.

So some aspects of the text’s origins might remain a mystery. But nevertheless, I do think this law should be used more actively as evidence, especially for the place of Latin within the Anglo-Saxon written legal sphere. It’s so rarely used by historians or others. I suspect that’s only partly a result of the unknown origins of the text – after all, early medieval historians aren’t usually in the business of ignoring evidence just because we don’t know much about it.

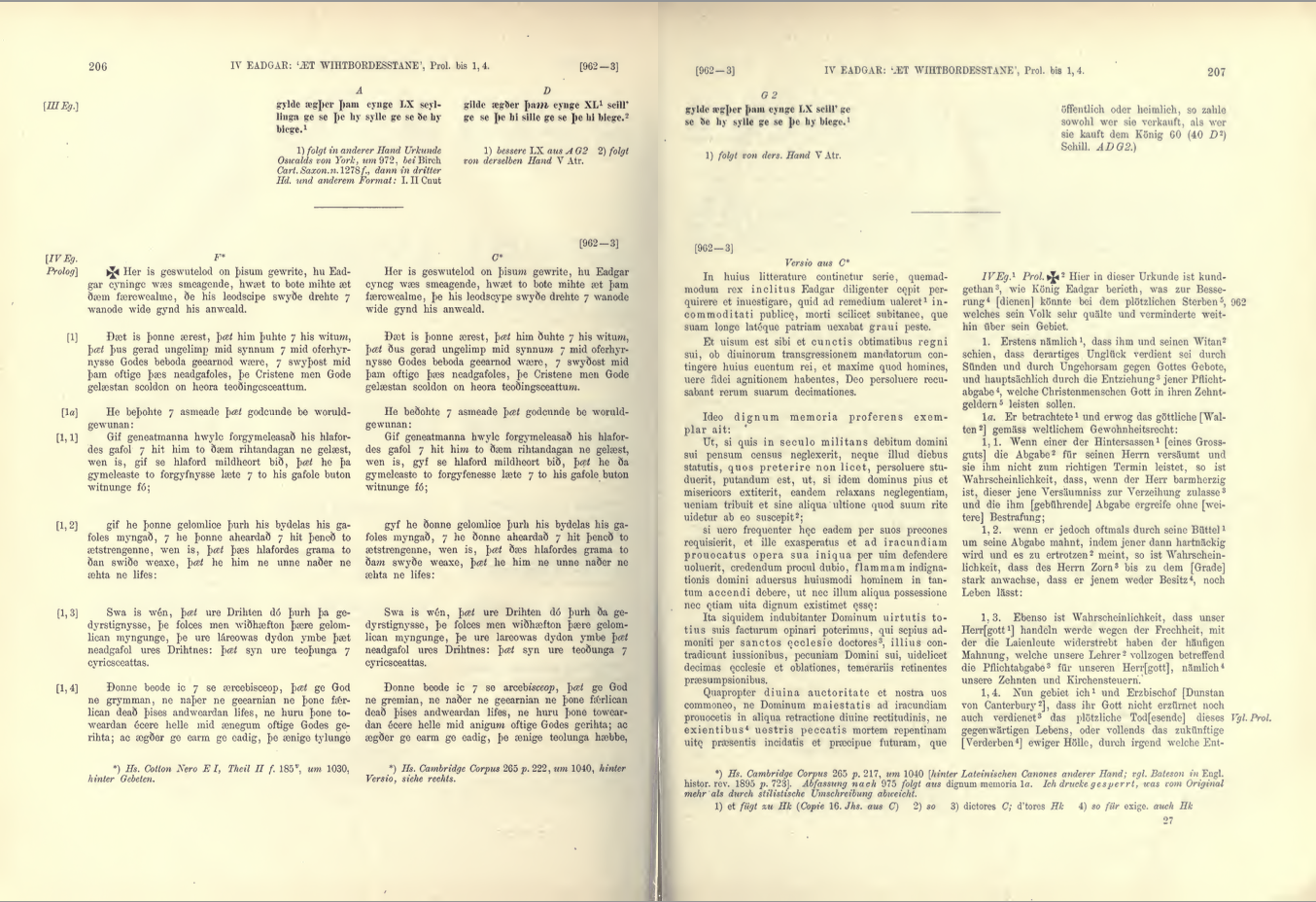

I think it’s just as much to do with the editions and translations historians use in our work. The most recent edition of Edgar’s laws (in fact, the most recent single-volume edition of all the laws and the standard edition for most of them) is that of Felix Liebermann from 1903. Here, IV Edgar Latin occupies the column (see the picture below) usually set aside for the Latin translations of Anglo-Saxon law made in the 12th century (known as the Quadripartitus collection). Most historians interested in pre-Conquest law (or other Anglo-Saxon history) usually don’t care about these (nor do most people working on the 12th century). It seems like readers might just assume that this Latin version is yet another post-Conquest translation. This has definitely happened in the Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources, which lists a word from IV Edgar Latin as coming from the 12th-century collection (s.v. ‘iustificatio’ sense 6).

Liebermann is the edition used by most historians the last century, and his relegation of IV Edgar Latin to this particular column seems to have had an effect. It was never included or picked up in the most recent English translation of the laws (A.J. Robertson in the 1920s) or other scholarship from that period. (Though, here there is also probably influence from the 19th- and early 20th-century idea of the strong and important connection between English law and English language, which I’ll also write about some other time). And it rarely features in scholarship now, nor are there any published translations. Hopefully, the translation I’ve published here might make it more accessible. Maybe someone can finally figure out what this strange text actually is.

A spread from Liebermann’s edition of IV Edgar, with the Latin text in the third column. Not always easy to spot what’s important!

A spread from Liebermann’s edition of IV Edgar, with the Latin text in the third column. Not always easy to spot what’s important!

-

There is no I Edgar — the decree which used to go by this name is no longer thought to have been written by Edgar and is now usually called ‘The Hundred Ordinance’. ↩

-

The treaty between Alfred and Guthrum (AGu) is the exception — the two extant versions of this text do not appear to be the result of changes made through later copying. For a similar practice in Carolingian Francia, see McKitterick’s The Carolingians and the Written Word. ↩

-

A version of VI Æthelred (translation coming soon) is in Latin and the laws of Ine might have been written in Latin too, see my article on that here. ↩